Out beyond ideas of right doing and wrong doing

There is a field.

I will meet you there.

from the Persian poet Rumi 1207-1273

*

In the 1st century BCE, in Jerusalem, two schools of Jewish thought — the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai — constantly argued matters of theology, ritual practice and ethics. The disciples of Rabbi Hillel and Rabbi Shammai engaged in over three hundred disputes, though Hillel and Shammai personally debated only three issues, one of which concerned the order of lighting Hannukkah candles.

Shammai said, “You start with eight candles on the first night and decrease to one candle on the last night.” Hillel said, “You start with one candle on the first night and increase to eight candles on the last night.”

Commentaries on this Subtraction v. Addition disagreement abound, but I’m most drawn to the words of the 17th century Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz. “The House of Shammai,” Rabbi Luntschitz taught, “are of the opinion that the Hanukkah lights represent the body. The body ages over time and gradually deteriorates. Just as a candle flame dwindles over time, so, too, does the human body. For this reason, we light the candles in descending order to acknowledge the diminishing of our strength.” Put another way, Shammai suggests that energy eventually runs out. The oil gets used up. Lamps go dark. (No kidding . . . )

Moving on, Rabbi Luntschitz wrote, “The House of Hillel are of the opinion that the Hanukkah lights represent the soul. Since the soul always matures, the Hanukkah lights are lit in ascending order to acknowledge our increased wisdom and the endurance of the Jewish people.” In short, Hillel suggests that we can always grow, add, and contribute to the world. (Someone please remind me of this when I’m still in my PJs at noon.)

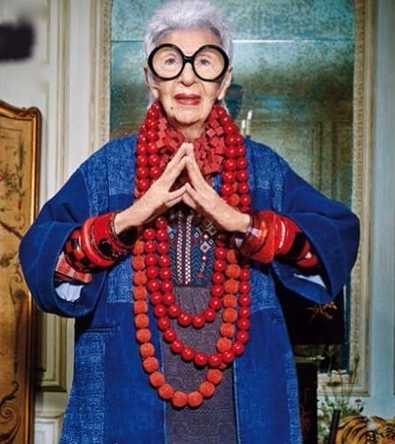

To support Hillel’s positon, let us now consider legendary style icon Iris Apfel who, at the age of 95, keeps adding stuff to her closet. A coat created from red and green rooster feathers;

red suede trousers slashed to the knees; shaggy goat-fur moonboots; bracelets made of plastic animal eyes; amber and turquoise and coral necklaces, the beads big as birds’ eggs. The 2005 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit, Rara Avis: Selections from the Iris Apfel Collection, made her an international star. Since the Met show, Iris created a lipstick line for M.A.C, jewelry for Home Shopping Network, taught at the U. of Texas and appeared in car commercials for Citroen. Just like the cruse of oil in the Hanukkah story, Iris Apfel is apparently inexhaustible.

On the flip side, Greta Garbo is the Shammai subtraction poster girl. She started big and then flamed out, turning her back on the Hollywood lights, retiring at thirty-six. Unlike Apfel, Garbo pared down to the minimum, her public appearances diminished to occasional walks on Manhattan streets, alone, in dark glasses, wearing no makeup, a hat pulled down over her aging face. “I am living my usual rut again,” she wrote in her later years. “Seeing nobody, never wanting anything . . .” Except to be left alone.

Jewish law almost always follows the rulings of Hillel — as they did with the Hanukkah candle lighting debate. Still, the Sages believed Shammai’s opinions were valid, too, which gives us permission to follow either Iris or Greta. We can choose to add to our lives, or subtract from our lives. To remain visible or become invisible. Pick what you will. Either way, you’ll get no argument from me.

In his sermon, Hillel and Shammai: How to Disagree, Rabbi Jonathan Kligler said, “I watch with dismay as our government grinds to a halt, held hostage by those who reject the very idea of respectful dialogue and creative compromise. (Let us) give up the fortress of being right, and walk out into the open field of possibility, knowing that we cannot by definition know all the answers . . .”

If I’m not home, you’ll find me in Rumi’s field.

There is a field.

I will meet you there.

from the Persian poet Rumi 1207-1273

*

In the 1st century BCE, in Jerusalem, two schools of Jewish thought — the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai — constantly argued matters of theology, ritual practice and ethics. The disciples of Rabbi Hillel and Rabbi Shammai engaged in over three hundred disputes, though Hillel and Shammai personally debated only three issues, one of which concerned the order of lighting Hannukkah candles.

Shammai said, “You start with eight candles on the first night and decrease to one candle on the last night.” Hillel said, “You start with one candle on the first night and increase to eight candles on the last night.”

Commentaries on this Subtraction v. Addition disagreement abound, but I’m most drawn to the words of the 17th century Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz. “The House of Shammai,” Rabbi Luntschitz taught, “are of the opinion that the Hanukkah lights represent the body. The body ages over time and gradually deteriorates. Just as a candle flame dwindles over time, so, too, does the human body. For this reason, we light the candles in descending order to acknowledge the diminishing of our strength.” Put another way, Shammai suggests that energy eventually runs out. The oil gets used up. Lamps go dark. (No kidding . . . )

Moving on, Rabbi Luntschitz wrote, “The House of Hillel are of the opinion that the Hanukkah lights represent the soul. Since the soul always matures, the Hanukkah lights are lit in ascending order to acknowledge our increased wisdom and the endurance of the Jewish people.” In short, Hillel suggests that we can always grow, add, and contribute to the world. (Someone please remind me of this when I’m still in my PJs at noon.)

To support Hillel’s positon, let us now consider legendary style icon Iris Apfel who, at the age of 95, keeps adding stuff to her closet. A coat created from red and green rooster feathers;

red suede trousers slashed to the knees; shaggy goat-fur moonboots; bracelets made of plastic animal eyes; amber and turquoise and coral necklaces, the beads big as birds’ eggs. The 2005 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit, Rara Avis: Selections from the Iris Apfel Collection, made her an international star. Since the Met show, Iris created a lipstick line for M.A.C, jewelry for Home Shopping Network, taught at the U. of Texas and appeared in car commercials for Citroen. Just like the cruse of oil in the Hanukkah story, Iris Apfel is apparently inexhaustible.

On the flip side, Greta Garbo is the Shammai subtraction poster girl. She started big and then flamed out, turning her back on the Hollywood lights, retiring at thirty-six. Unlike Apfel, Garbo pared down to the minimum, her public appearances diminished to occasional walks on Manhattan streets, alone, in dark glasses, wearing no makeup, a hat pulled down over her aging face. “I am living my usual rut again,” she wrote in her later years. “Seeing nobody, never wanting anything . . .” Except to be left alone.

Jewish law almost always follows the rulings of Hillel — as they did with the Hanukkah candle lighting debate. Still, the Sages believed Shammai’s opinions were valid, too, which gives us permission to follow either Iris or Greta. We can choose to add to our lives, or subtract from our lives. To remain visible or become invisible. Pick what you will. Either way, you’ll get no argument from me.

In his sermon, Hillel and Shammai: How to Disagree, Rabbi Jonathan Kligler said, “I watch with dismay as our government grinds to a halt, held hostage by those who reject the very idea of respectful dialogue and creative compromise. (Let us) give up the fortress of being right, and walk out into the open field of possibility, knowing that we cannot by definition know all the answers . . .”

If I’m not home, you’ll find me in Rumi’s field.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed